Who we are

The explosion of 1948

The clock at Gate 1 stopped at 3:43 p.m. The explosion that shook the BASF site in Ludwigshafen at this time on July 28, 1948 wrought unthinkable destruction in a place that was still being rebuilt following the Second World War and which was still under French occupation three years after the end of the war. The disaster created a widespread stir as a result of extensive international press coverage. Similarly, aid also came from virtually all over the world after the explosion, and soldiers from both the French and the adjacent American occupation zones immediately made their way to the site to assist.

Another gas cloud explosion

The old administration building Lu 10 indicated the sheer scale of the destruction. The first image shows the undamaged building in 1938, while the second photo taken from further away shows it after the explosion in 1948.

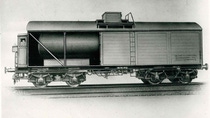

As was the case in the gas cloud explosion of 1943, a tank car was once again involved. On July 28, 1948, the large pressurized tank car “Halle 562 795” was standing at the Anilinfabrikstraße/Bleistraße crossing, between buildings Lu 47 and Lu 21. It was left there at 5:45 a.m. and was exposed to high temperatures during this especially hot day in July. The tank car was loaded with around 30 metric tons of dimethyl ether – when it burst, the liquefied gas streamed out and evaporated. The mixture of dimethyl ether and air then ignited, causing an explosion that claimed 207 lives and injured 3,818 people, some of whom were seriously injured.

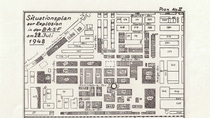

The extent of the destruction caused by the explosion can be seen on this site plan, which shows totally destroyed (“total zerstört”), severely damaged (“schwer beschädigt”) and moderately damaged (“mittel beschädigt”) buildings. [Source: Landesregierung Rheinland-Pfalz (Ed.): Explosions-Katastrophe in der Badischen Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik Ludwigshafen am Rhein am 28.7.1948, Kaiserslautern 1949]

The factory premises resembled a rubble field within a radius of 200 meters around the explosion center. Around 20 buildings on the site premises were completely destroyed by the explosion, while a further 120 were damaged severely. In addition, countless factory buildings had roof damages and broken windows. Overall, a roof area of 185,000 square meters had to be relaid on the site premises, while 61,400 square meters of windows had to be reglazed. The city of Ludwigshafen, in particular the north of the city and the Friesenheim district, were also damaged by the shockwave triggered by the explosion. Almost 5,000 buildings were affected in these parts of the city, with around half that number also being damaged on the opposite side of the Rhine in Mannheim.

Upon the horrific bang of the explosion, aid arrived quickly: People flooded in from the site, the city and the region. The US and French occupying forces were also on-site quickly. Much like the disaster itself, this act of remarkable solidarity transcending zone boundaries soon made headlines. [Source: city archives Ludwigshafen am Rhein, photographer: Hans Wagner, Haardt]

Overpressure due to overfilling?

Various groups were involved in the investigations into the cause of the disaster: the public prosecutor’s office, the criminal investigation police and their French counterpart, the Sûreté nationale. Naturally, the industrial inspectorate and the employers’ liability insurance association were also involved. In addition, two committees were set up: the seven-head parliamentary investigating panel for the state of Rhineland-Palatinate and, on the initiative of the French occupying force, an international investigation commission.

What caused tank car “Halle 562 795” to burst? A conclusive answer to this question was never found at the time: The experts came to the conclusion that it was caused by a series of unfortunate events. According to them, the possible causes were an incorrect rating for the tank car capacity, the high temperature on July 28, 1948 and a weak spot on the upper longitudinal welded seam of the tank. Similar to the disaster of 1943, the damage pattern indicated a tank that had seemingly burst due to overpressure of the tank interior.

In an announcement, the BASF workforce was informed of the final report of the parliamentary investigation commission in its original wording – and was assured that additional safeguards were already being implemented at the site.

The investigators concluded that tank car “Halle 562 795” was not overfilled under the definition of the existing specifications of the German Compressed Gas Regulation (Druckgasverordnung). However, it was deemed probable that the capacity of the tank car was actually lower than the officially rated capacity. Accordingly, the public prosecutor’s office did not believe there was any violation of the applicable safety regulations. “The bursting of Halle tank car no. 562 795 can be explained by a liquefaction of the dimethyl ether contained within. This liquefaction was the result of overfilling, due to the fact that this tank car actually had a lower volume than that specified by the calculated capacity on the official rating plate,” explained the international investigation commission in its report submitted in January 1949.

30 tons of highly flammable material

Experts at the time were surprised by the unusually severe explosion and the extent of the destruction caused. It involved a colorless, highly flammable liquefied gas: dimethyl ether. The dimethyl ether in the tank car “Halle 562 795” at the center of the disaster was produced while manufacturing methanol at the Oppau site and was filled there on July 10, 1948. At the Ludwigshafen site, the 30 metric tons of dimethyl ether were to be processed into dimethylaniline – a dyestuff intermediate that had been manufactured from aniline and dimethyl ether in building Lu 21 since 1937.

Design of a typical four-axle tank car for liquefied gas with weather protection enclosure, as was used to transport dimethyl ether in 1948. A wooden jacket was designed to protect the tank car from direct sunlight.

The wreckage of the burst tank car “Halle 562 795”

Explosives and other rumors

As differing political interests clashed ahead of the looming Cold War between the Western and Soviet occupying forces, the explosion was presented to the public in very different ways. This allowed false reports and rumors to enter the public consciousness. One rumor was that the explosion had been caused by secret experiments conducted by the French occupying power at the BASF site in Ludwigshafen. The numbers of victims also varied greatly in the beginning – possibly as a result of uncertainty about the events running up to the disaster and because of a desire to report to the public as soon as possible. The rumor was also spread that explosives were being manufactured in Ludwigshafen, even though there was no crater on the site premises that would have been created by such an explosion.

A picture of destruction after the disaster – but no crater [Source: BASF Corporate History; photographer: unknown]

The disaster as viewed from the Rhine: A fireboat heads toward the BASF site premises on July 28 [Source: city archives Ludwigshafen am Rhein; photographer: Roden Press, Mannheim]

"Like a fireball spreading"

The scene of the 1948 disaster indicates that it must have been a deflagrative explosion event, explains Dr. Vera Hoferichter, Head of BASF Gas Phase Explosions & Ignition Sources. In an interview, she describes what that means and how the filling regulations of the time would be viewed today.

In the wrong place at the wrong time

A total of 207 people lost their lives on this day. Two of the fatalities were representatives from the French administration, 176 were employees of the Ludwigshafen site and 24 were working there for external companies (contractors). Five people not on site premises were also killed, including a four-year-old girl.

Of the 3,818 people who were injured, around 500 people were severely injured and required hospital treatment as inpatients. The overwhelming majority of those injured were company employees, while 778 were employees from external companies or people who were not on site premises – the explosion not only destroyed parts of the site, but also inflicted damage in the residential areas surrounding it. The shockwaves caused by the explosion were felt far beyond Ludwigshafen, and the cloud of smoke was visible for miles. Roofs collapsed and window panes shattered. The tremendous bang and its consequences traumatized an entire city.

But some could also count themselves fortunate: At the time of the explosion, around 600 employee representatives were attending a meeting in the Feierabendhaus, a BASF building used for events that is not situated on the site premises. Presumably, many of them would otherwise have been close to the explosion and would have been caught up in it. One of the representatives was Maria Tomalik’s father, Ludwig Zimpelmann. Maria Tomalik was ten years old at the time and was at home in Anilinstraße, very close to where the explosion happened.

It was summer and Maria Tomalik (*1938) enjoyed being able to walk barefoot. On July 28, 1948 the ten-year-old girl was wearing an airy summer dress and was darning socks in front of her parents’ house in Anilinstraße, not far from the entrance to the municipal hospital in Bergmannstraße, when she heard a sudden bang. Window panes shattered, tiles fell from the roof and her bare feet were bleeding. The horrific scenes that Maria Tomalik witnessed on that day still affect her today. However, she remained in Ludwigshafen and went on to work in the laboratory at BASF.

"And then it came rolling up from Gate 1, the big wave. It carried gravel in it, and sand, and glass.”

Heinz Müller (1929–2022) has lived in Limburgerhof not far from Ludwigshafen since childhood. Starting in early 1948, he had been working in the carpenter’s workshop for office and laboratory furniture on the BASF site premises, which at that time was helping to rebuild the site after it had been damaged during the war. At the very moment the explosion occurred, the then 19-year-old was close by and was working on installing a desktop; the fact that he was underneath it at the time presumably spared him from a worse fate. One of his colleagues, who was in the workshop at the time of the explosion, was killed. Müller worked his way up to the level of master carpenter in the following years, spending his entire working life at BASF.

“Not much hit me. Almost everything fell around me, onto the laboratory bench, in the aisles.”

„A vast wealth of experiences“

Eyewitness reports allow us to experience historical events on an emotional level and bring us closer to them. In addition, they offer the subjectivity that we need to draw a complete picture of what happened “back in the day.” The press coverage of 1948 was dominated by eyewitness reports and personal accounts of the disaster as well. An appeal by BASF in 2022 for accounts also showed just how many people can still remember the disaster they had experienced as a youth or child. Dr. Isabella Blank-Elsbree, Corporate Historian at BASF Corporate History, describes the importance of contemporary witnesses and the idiosyncrasy of memory.

Search, rescue, assistance

The first search, rescue and aid measures began immediately. Doctors, nurses and Red Cross responders made their way to the place of the disaster from all over the region, with the border between the French and American occupation zones suddenly ceasing to matter.

The fire brigade and police also rushed to provide help, as well as soldiers from the two occupying forces on both sides of the Rhine. The deployment of responders is often retrospectively described as being unprecedented. Organized under the so-called “Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen,” the relief efforts and compensation for victims and family members are also remarkable.

Without hesitation

A large number of BASF employees also provided immediate assistance. Even though some of them had been injured themselves and given rudimentary medical aid, they joined the efforts to care for or transport injured people, as well as helping to search for and recover victims. All responders put themselves at considerable risk: Blocked transport routes, fires, lots of smoke and the ever-present risk of further explosions made the tasks of the cleanup, rescue and search teams more difficult.

Solidarity transcending zone boundaries

“The immediate aid measures were performed by the occupying forces,” explains Dr. Stefan Mörz, head of the City Archives in Ludwigshafen (Stadtarchiv Ludwigshafen a. Rh.). In an interview, he speaks about an accident that would quickly become a media event, but that also became a shining example of comprehensive short and long-term aid measures that brought people together beyond zone boundaries in the spirit of action and solidarity.

Material aid

Aid also reached those affected quickly in the form of monetary and non-monetary donations to BASF, the city administration or, for example, the hospitals – and came from all over Germany and even from abroad. Immediately after the disaster, BASF provided a sum of DM 100,000. The donations were pooled by Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen, which organized the services and measures for material aid. In total, Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen collected around DM 2.75 million, as well as almost 150,000 kilograms of essential and luxury foods and goods, in addition to clothing, shoes, dressing material, medicines, building materials and construction equipment. One important element of this aid was the long-term financial aid for bereaved family members and injured people who were no longer able to work, to which Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen and BASF contributed. The monetary and non-monetary donations organized by Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen were also used to rebuild or repair buildings not situated on the site premises.

“Hilfswerk will help you:” Posters provided information to people not on site premises at the time of the explosion but who suffered loss and/or injury about matters including aid for bereaved family members and compensation for lost wages. [Source: City Archives Ludwigshafen am Rhein]

Special Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen stamps with a surcharge of 30 to 50 pfennigs were released in October 1948 and enjoyed successful sales. These raised just under DM 275,000, which went to Hilfswerk Ludwigshafen.

Like a wildfire

In 1943, the Nazi dictatorship meant that hardly anyone outside the city heard about the explosion on the site premises of the then I.G. Farben in Ludwigshafen. In 1948, however, news of the explosion at BASF in July of that year spread like a wildfire throughout Germany – and even received international press coverage.

Photographers and journalists came from all over to report on the disaster. Augmented by the descriptions of eyewitnesses and people who were affected by the blast, these valuable descriptions illustrate the disaster in all its horrifically vivid terms. The disaster became a media event, or even a spectacle, which was viewed through the lens of the nascent Cold War and instrumentalized to this effect.

Because the explosion of 1948 occurred in a Germany governed by four occupying forces, the event quickly gained international prominence. Prof. Katja Patzel-Mattern, economic and social historian at Heidelberg University, shines a light on the idiosyncrasies of the press coverage on the explosion. She also explains why we report differently today and, above all, why we would document the images of the disaster differently.

New wounds

There is an overwhelming wave of sympathy: On August 2, 1948, between 15,000 and 20,000 people (the specific number varies depending on the source) took part in a state ceremony at Ludwigshafen’s market square in honor of the victims of the explosion – with attendees including high-ranking state and military representatives. The church memorial service at the main cemetery in Ludwigshafen was attended by 6,000 people.

The shock was deeply felt. In his eulogy, the Works Council chairman Ernst Lorenz also referred to the two previous explosions in Oppau and Ludwigshafen: “(…) It almost appears that rubble and debris are to be a constant companion in the struggle of a BASF employee. For many of the people attending today’s memorial, the memory of the terrible disaster of 1921 is still fresh in their minds, and they have not yet been able to fully move on from the emotional and material suffering it brought. The year 1943 cut new wounds, which were then exacerbated by the war and everything that came with it.”

On the first anniversary of the explosion, the sirens at BASF sounded at 3:43 p.m. to start a minute’s silence for the victims. Prior to this, employees were invited to a memorial service at the main cemetery in Ludwigshafen. In the following years, BASF and the City of Ludwigshafen commemorated the victims of the 1948 explosion by laying wreaths on the anniversary of the disaster and on All Souls’ Day / All Saints’ Day. In an official ceremony on July 28, 2023 – the 75th anniversary of the disaster – BASF and the City of Ludwigshafen will also commemorate the victims of the 1943 disaster, which happened 80 years ago on July 29.

Invitation to the memorial service on the first anniversary of the disaster. As a sign of the site’s “sympathy and solidarity,” BASF also sent personal letters in 1949 to the families of the victims and to those who were wounded and still unable to work (or disabled as a result of their injuries). The letter also detailed the commitment to take on the children of those affected as apprentices at BASF.

Invitation of BASF and City of Ludwigshafen to the memorial service on July 28, 2023. Together, they will commemorate the two explosion events that happened 75 and 80 years ago.