Stefan Lamotte in his laboratory with the high-performance

HPLC instruments (HPLC = High Pressure Liquid Chromatography).

Who we are

What holds the world together at its core? Even as a child, Stefan Lamotte was fascinated by finding out what was behind things. His curiosity led him to pursue a doctorate in chromatography, a chemical analysis method used to separate and precisely determine the individual components of mixtures of substances. This is how he finds answers to why something works the way it does – and today, as an expert in analysis, he and his team ensure the quality of various BASF products.

It must be said clearly: If we were to do a bad job in analytics, people would encounter harm. After all, many of our products, such as superabsorbents for diapers, dietary supplements and laundry detergent additives, come into direct contact with humans. It's only logical that we monitor our products as closely as possible.

To do this, our analytical methods have to be very, very good. I am happy to take on this great responsibility. We have a strong network of experts and a great deal of experience, which we leverage to ensure our products are safe. That is a very good feeling.

Stefan Lamotte is an expert in analyzing samples of a wide variety of products down to the smallest detail – and also breaks new ground in the process.

Simply putting it, chemistry is incredibly complex. The more you know, the more you realize how little you actually know. And then you always want to know more. Ever since I first got involved with chromatography – the separation of a mixture of substances – in my second semester, I knew: this is what I want to do. It was in this moment, I became fascinated by the technology and the possibility of going deeper into the interactions between different substances through separation. Even today, after 30 years in this field, it happens at least once a week where I don't understand something; that's what drives me. Often enough, the idea for a solution comes to me while I'm falling asleep or in a conversation about a completely different topic.

Stefan Lamotte in his laboratory with the high-performance

HPLC instruments (HPLC = High Pressure Liquid Chromatography).

I joined BASF relatively late, in my mid-40s. Looking back, that was a real stroke of luck. After completing my doctorate, I worked for many years as an expert in liquid chromatography (HPLC) in a small, specialized company, where I developed and marketed separation columns crucial for separating a sample. In this job, I was able to build a broad network. After I had to go on short-time work during the economic crisis in 2008, this network helped me find a job at BASF as an HPLC expert. The chemistry was right away clear, and figuratively speaking. Today, I still use the separation columns I developed myself back then here in the BASF lab for certain applications.

The separation column is the heart of the HPLC system. Inside, the samples are split into their individual components.

Every new question and every sample present us with new challenges, and that's what I find so exciting. For example, we have to make sure there are no polyaromatic hydrocarbons in monomers that are later used for polymers in children's toys. We look at the substances down to the smallest detail in our analyses, in some cases going down to the range of a billionth, to be absolutely certain a product does not contain any impurities; it's like looking for the oak leaf on the one-cent coin across the entire BASF site in Ludwigshafen – which is as large as 1400 soccer fields.

The most wonderful thing for me is to make something possible that was not possible before. For example, the first successful separation of a substance from a complex mixture is an overwhelming moment. It feels like a mini "man on the moon" moment, because the first time we successfully separate a substance, we are entering uncharted territory.

By separating individual components, we generate valuable information about their properties and interactions. In this way, we offer a better understanding of chemical compounds and help optimize production processes and bring new products to market. For example, we developed an analytical method that was able to determine hydrophobic impurities in a pharmaceutical excipient and thus improve the quality of the product. Our customer, a large pharmaceutical company, was very satisfied.

Stefan Lamotte often comes up with the best ideas for solving a challenge in discussions with colleagues.

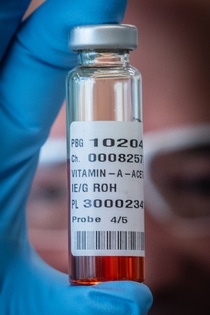

Vitamin A is a vital nutrient necessary for numerous biological processes such as vision, immune function, cell differentiation and embryonic development.

BASF supplies the World Health Organization (WHO) with vitamin A to enhance staple foods such as vegetable oils and counteract the life-threatening undersupply of the vitamin in poor regions. Oil mill operators add the vitamin A produced by BASF to their oil and then test it to see if it has the optimal vitamin content. In the case of soybean oil, determining the vitamin A content with the supplied rapid test, a color reaction, did not work.

To solve this problem, we developed a new analytical method in collaboration with a PhD student at the University of Giessen. This simple test determines the vitamin A content by separating the vitamin from the oil matrix using thin layer chromatography. The separation requires small amounts of water and acetone as solvents, as well as a freely available app and a smartphone for evaluation. This makes the test more environmentally friendly and less expensive than the conventional method.

We have patented the new method so no one can commercialize it and it is available for free to everyone. I think it's simply impressive how diverse the areas of application for chromatography are.

In the laboratory itself, we work to use as little energy and raw materials as possible in our analyses. For example, in some processes we at least partially replace organic solvents with supercritical CO2, that is carbon dioxide, which combines properties of gas and liquids under high pressure and temperature. This allows us to speed up our separations and at the same time reduces our solvent waste.

Similarly, we are looking at the extent to which we can miniaturize our HPLC system. So, we make it much smaller, and thus require much less solvent and energy for the analyses. Automation is also constantly advancing. We have been working successfully side-by-side in the laboratory for several years with robots that we have programmed ourselves. They prepare the samples for us and conduct simple reactions before chromatography.

I would say the importance of analytics in general is just growing. Society is facing many major challenges, for example when it comes to toxic components in products and how we can determine and ultimately eliminate these contaminants. It motivates me and my colleagues immensely to find solutions to these regulatory and environmental analytical challenges and thus contribute to a sustainable future.

Stefan Lamotte and his team have programmed robots themselves to assist in the preparation of the samples.