Who we are

8 Traces

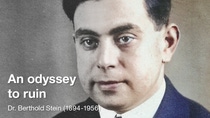

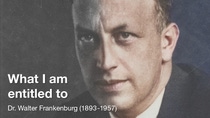

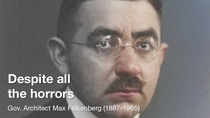

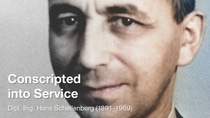

To mark the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp on January 27, 2025, BASF has traced the stories of eight people who met eight very different fates.

We follow the often-faint traces of individuals employed at the Ludwigshafen and Oppau plants of I.G. Farben, now BASF SE’s main site, who were persecuted, discriminated against or ostracized under the Nazi regime. The idea is to use these individual stories to commemorate all those who suffered so immeasurably between 1933 and 1945. After all, long before the Nazi regime began systematically murdering persecuted groups, it gradually stripped them of their rights and destroyed their social, economic and cultural existence.

German Jews by faith and/or descent played an important part in the foundation of BASF. One of the founding fathers was Seligmann Ladenburg, a banker from Mannheim. Heinrich Caro, one of the most important chemists of the early years, was in charge of scientific research at BASF from 1868 to 1889, making significant contributions towards the coal tar dye chemistry. At the Ludwigshafen and Oppau plants, which became part of the newly formed I.G. Farbenindustrie AG in 1925 through a merger, the year of 1938 at the latest brought devastating certainty. The Central Committee of I.G. Farben, which made all the key personnel decisions, resolved in April, under the influence of Nazi Party’s increasingly radical policies on Jews, to dismiss all remaining employees who were Jewish or classified as such by state decree. Employees whom the Nazi regime defined as “half-Jews” [Nazi term] or who were in “mixed marriages” (with “Aryan” spouses) [Nazi term] increasingly suffered discrimination, exclusion and persecution. The same applied to Sinti and Roma, as well as political opponents of the regime.

The dismissals lost the Ludwigshafen and Oppau plants valuable employees, key expertise and esteemed, loyal colleagues. Some managed to escape abroad, uprooted and facing financial ruin; others were deported and had to perform forced labor. Marie Schuster perished in a concentration camp, while others lost relatives. In rare exceptional cases, highly skilled Jewish staff who had been forcibly retired and left to claim “waiting pay” by I.G. Farben survived in Germany under the protection of a “privileged mixed marriage.” A few employees classified as “half-Jewish” by the Nazi state were able to continue working at the Ludwigshafen and Oppau plants until the war ended in 1945.

The plant management at Ludwigshafen and Oppau largely adopted an indifferent stance toward the groups affected by discrimination, disenfranchisement and persecution, limiting themselves to handling matters in the manner considered formally “correct” at the time. They adhered to regulations, particularly contractual provisions, such as those concerning waiting pay or compensation for waiting periods. There are no known cases of extreme discrimination, nor of special support.

Due to the incomplete records available, this search for traces only amounts to an approximation. It is fragmentary, sketchy, and detailed only in places. None of these stories can be completely told based on our current knowledge – nor can we be certain that we have identified all the names of employees persecuted by the Nazis. In most of the cases that we have been able to reconstruct, the individuals affected were highly skilled workers who were Jewish or classified as such by the Nazi definition.

Memorial book

2025 will also mark the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. In the brutal Nazi apparatus, the Holocaust was by far the greatest crime against humanity. More than six million Jewish men, women and children from all over Europe were murdered. This search for historical traces also serves as a reminder that the societal and legal groundwork for the persecution of racial and political opponents of the regime unfolded not out of sight, but in the midst of people’s professional and private lives.

In our memorial book, we have compiled all the fates identified by BASF Corporate History to date.