Who we are

Carl Bosch (1874–1940) – Nobel Prize laureate, scientist, business leader

150th anniversary highlights

An exceptional, unconventional talent makes history

Making “bread from air” – the Haber-Bosch process achieves the seemingly impossible by synthesizing ammonia. Carl Bosch, who went on to win the Nobel Prize, was chairman of the Board of Executive Directors at BASF and later I.G. Farbenindustrie AG (commonly known as I.G. Farben). He was also accountable for developing further high-pressure processes. As a senior manager, the decisions he made proved to have far-reaching consequences during the two world wars, yet the man himself remains an enigma. This webpage takes a look at his legacy spanning highlights from BASF Corporate History.

It was a scientific and technological sensation: With the Haber-Bosch process, Bosch had managed to synthesize ammonia by binding atmospheric nitrogen for use in the industrial-scale production of fertilizer. He thus solved one of the most pressing issues of his time, the so-called nitrogen problem. Harvests had to be significantly increased in order to keep pace with the growing population. However, the natural deposits of the nitrogenous fertilizers required for this, above all Chile saltpetre, were in danger of being exhausted. BASF and Bosch counteracted this with large-scale ammonia synthesis. It revolutionized agriculture by ushering in the age of mineral fertilization. With it, Carl Bosch created the basis for providing food for a large part of the world's population.

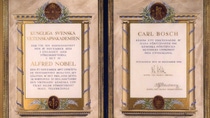

What’s more, with the world’s first ammonia plant, the BASF site in Oppau introduced high-pressure catalysis to the chemical industry in 1913. The development of further high-pressure syntheses is also closely associated with the name of Carl Bosch. His accomplishments earned him several honorary doctorates and numerous awards, including the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1931. By this point, he was already Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors and the driving force behind BASF (1919–1925) and I.G. Farben respectively (1925–1935). From 1933 onward, strategic business decisions saw I.G. Farben forming ties with the Nazi regime, although Bosch personally opposed the latter’s persecution of Jewish scientists. Known for his wide-ranging passions and boundless energy, Bosch battled severe depression, particularly in his final years.

Carl Bosch the man

Bosch was a passionate scientist, chemist and engineer through and through.

A brilliant scientist, Bosch had no patience for conjecture. Yet much of our view of him today is shaped by speculation. His achievements as a scientist and business leader speak for themselves. But we have little insight into his motives, and few personal accounts of him exist. At the same time, a wealth of anecdotes have built up around him that have since solidified into seemingly established truths. Records of his achievements and accounts from his contemporaries paint a contradictory, multifaceted picture.

Biographical overview

Practical with wide-ranging interests: Education, studies and doctorate

Bosch was born on August 27, 1874 in Cologne, Germany. Diverging from the traditional path, he attended the vocationally-oriented secondary school in Ober rather than the classical humanistic German Gymnasium. The young Bosch then completed a year of practical training at the Marienhütte ironworks in Kotzenau, Silesia. With this experience under his belt, he enrolled at the Technical University in Berlin-Charlottenburg to study metallurgy (encompassing materials engineering) and mechanical engineering. However, the gifted student found that metallurgy and mechanical engineering still relied too heavily on rules of thumb rather than precise equations. This led him to transfer to Leipzig University, where he majored in chemistry, driven by his passion for precision research. Bosch completed his studies in 1898 at the age of around 24, earning a doctorate and top marks.

He then briefly worked as a sales assistant in the Analytics department under his doctoral supervisor Johannes Wislicenus (1835–1902). Rather than pursuing a scientific career, Bosch applied for a chemist position at BASF, which at the time was by far the largest chemical company in the German Empire. BASF had caused quite a stir in scientific circles on a number of occasions, most recently in 1897 with its industrial-scale synthesis of indigo.

Bosch at BASF and I.G. Farben: Climbing from the lab to top management

Bosch spent his first working day at BASF on April 15, 1899 in the main laboratory like all new chemists. But within the same year, he moved to the phthalic acid factory, where he took charge of its expansion. His first encounter with the challenge of industrial nitrogen fixation was in 1900.

From scientist to corporate leader

BASF recognized and nurtured his talent, ultimately propelling him to the helm of what was one of the largest companies in Germany at the time. Bosch became an authorized signatory in 1911 and a deputy board member in 1914. During the First World War (1914–1918), he promised to supply German military leadership with the crucial precursor material saltpeter for munitions production in what became known as the “Salpeterversprechen” (“Saltpeter Promise”). Bosch became a full board member in 1916. At the end of 1918, he represented the chemical industry at the armistice negotiations during the Spa Conference held in Belgium. In 1919, he attended the Paris Peace Conference held at Versailles as an expert for the German delegation. Bosch became Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors in the same year.

From the Management Board to the Supervisory Board

This development saw Bosch becoming more a leader than a mere scientist. In this capacity, he spearheaded the merger of leading German chemical companies into I.G. Farben, becoming its first Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors in 1925. It was primarily the high-pressure projects championed by Bosch that ultimately brought I.G. Farben into direct affiliation with the Nazi regime from 1933 onward and culminating in a close-knit economic partnership. In 1935, Bosch stood down from his role in the group’s day-to-day operational management and assumed the role of Chairman of the Supervisory Board. He passed away in 1940, sparing him from witnessing I.G. Farben’s involvement and culpability in the Nazi system of forced labor and its method of “extermination through labor.”

Long committed to scientific advancement in his personal life and having held numerous roles, Bosch was appointed President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science (now the Max Planck Society) in 1937. Worn down by illness, excessive alcohol consumption and depression, Bosch died on April 26, 1940.

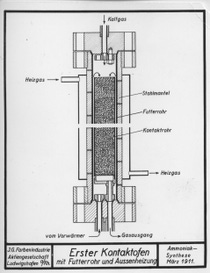

Synthesis of ammonia

The world’s first ammonia synthesis plant went into operation on September 9, 1913 at the Oppau site. This marked the start of high-pressure catalysis in the chemical industry. It was a scientific and technical feat that had previously been considered impossible by experts, with the exception of Bosch. “I believe it can be done.” This legendary quote is attributed to him. Drawing on his expertise in metallurgy, mechanical engineering and chemistry, Bosch was confident that he could transform a laboratory-scale process developed by Fritz Haber (1868–1934), a professor at the Technical University of Karlsruhe, into an industrial process.

This came after years of failed attempts by various chemists to find the coveted key to creating “bread from air” through nitrogen fixation. Plants rely on fixed nitrogen for improved growth and higher crop yields.

In early 1900, BASF tasked Bosch with testing a process developed by Wilhelm Ostwald, an expert in the field of physical chemistry and future Nobel Prize laureate in Chemistry. His results, however, could not be replicated, leading to a dispute in which Bosch was ultimately proven right. With this, he had passed his first major test, earning him the recommendation that he be given greater responsibilities. Three years later, he was commissioned to develop his own process for industrial nitrogen fixation. Despite some successes, including in collaboration with the chemist Alwin Mittasch (1869–1953), a breakthrough had yet to be achieved. Then BASF heard about Fritz Haber’s promising work.

Challenges: High-pressure team work

In 1908, BASF agreed to partner with Professor Fritz Haber in the field of nitrogen. Just one year later, he demonstrated his ammonia apparatus to BASF representatives. It was convincing. Bosch was appointed to lead the new BASF megaproject of industrializing Haber’s ammonia synthesis process. However, Haber’s process parameters presented huge challenges that represented unchartered territory in the chemical industry. The process involved nothing less than creating a catalytic reaction under extreme pressure and high temperature.

Briefly set in relation: Nitrogen, ammonia, nitric acid, saltpetre, nitrates

Nitrogen (N) is the main component of air. In its elemental form, it cannot serve as a plant nutrient, but must be present in bound form. The synthesis of ammonia (from atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen) using the Haber-Bosch process created the conditions for this on an industrial scale.

Ammonia (NH3) and nitric acid (HNO3) are among the most important basic materials in the chemical industry. Nitric acid has been produced by catalytic oxidation of ammonia since 1906. Platinum was used as a catalyst, which limited production capacity until BASF developed a new process with an iron catalyst in 1914.

Saltpetre is the trivial name for some naturally occurring nitrates. Until the introduction of the Haber-Bosch process, saltpetre was the only source of large quantities of nitrogen compounds. Chile saltpetre (sodium nitrate, sodium salt of nitric acid) is the most important naturally occurring nitrate with the largest deposit in Chile.

Nitrates (NO3), including ammonium nitrate (NH4NO3) and sodium nitrate (NaNO3), are salts of nitric acid (HNO3) and serve as a nutrient (nitrogen source) for plants.

Benefits laced with darkness

Ammonia synthesis enabled the production of mineral fertilizers, but also served as an essential component in nitric acid production, which was crucial for sustaining munitions production during World War I. As a result, it became a focal point discussed during the Paris Peace Conference, in which Bosch also participated. One of the largest industrial disasters in history occurred in Oppau in 1921, showcasing the complex, double-edged nature of industrial modernity replete with all its benefits, inherent darkness and ambivalence.

New high-pressure syntheses

High-pressure technology significantly shaped the chemical industry during the interwar period. Bosch had established BASF as a pioneer in this field in 1913. As Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors, Bosch further extended the technological lead of BASF and, from 1925, of I.G. Farben in this field. In 1931, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his contribution to the invention and development of chemical high-pressure processes. However, these were also of particular importance in the armaments and war economy of the National Socialists.

Freedom and advancement of science and research

Commitment on several levels

Throughout his life, Bosch saw himself first and foremost as a scientist and engineer, and only later as a corporate leader. He also had a wide range of scientific interests that he pursued in his private life, notably in natural history collections and astronomy. As Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors, he oversaw significant investments in research and development, convinced that the long-term survival of BASF, and later I.G. Farben, hinged on making scientific and technical advancements. Success proved that Bosch's strategy was right. Within the mere ten years under his leadership, I.G. Farben grew into one of the most diversified chemical companies in the interwar period.

New research facilities at BASF

Bosch was instrumental in founding two research facilities closely associated with ammonia synthesis. His proposed “Agricultural Research Station Limbergerhof,” now the BASF Agricultural Center Limbergerhof, opened in the spring of 1914. It was here that BASF systematically tested the efficacy of its new nitrogen fertilizers, adhering to its tradition of application-focused product testing. A second facility followed in 1917 in the form of a fully equipped ammonia laboratory under the direction of Alwin Mittasch, (1869–1953), catalysis expert and Bosch’s longest-serving employee.

Engagement beyond the company

Bosch is considered one of the most important and powerful patrons of science. From 1933 to 1935, he was Chairman of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians (GDNAE), Germany’s oldest and largest interdisciplinary scientific association. From 1937, he was President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, the predecessor of today’s Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. He also financially backed numerous research projects, both personally and through his company. Bosch strongly advocated for the freedom of science and research, a position he resoundingly articulated in two public speeches in 1934 and 1939. At the time of his death in 1940, Bosch was a member of 42 German and foreign scientific societies.

Advocacy for Jewish scientists

Consistent with his stance on the freedom of science, Bosch advocated for Jewish scientists to retain their roles after the Nazi rise to power. The “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service,” worded in the antisemitic, racist tones of the Nazis, made provisions for the expulsion of Jewish scientists in April 1933 from public service. It was not long afterward that Bosch met Adolf Hitler in person for the first time. Bosch is believed to have expressed his concern for Germany’s future competitiveness if outstanding scientists were forced to leave the country. Hitler is reported to have abruptly ended the conversation with the following words directed at Bosch: “The Privy Councilor wishes to leave!” At least according to his biographer, Karl Holdermann, this is how Bosch is said to have later recounted the encounter to trusted friends.

There is evidence that Bosch advocated for a number of individual Jewish scientists to remain in their positions or supported them in other ways. Such individuals include the physicist Lise Meitner (1878–1968), the astrophysicist Erwin Finlay Freundlich (1885–1964), the geochemist Victor Moritz Goldschmidt (1888–1947), the biochemist and Nobel Prize laureate Otto Meyerhof (1884–1951), the mathematician, physicist and later Nobel Prize Laureate in Physics Max Born (1882–1970) and the physicist Fritz London (1900–1954).

Solidarity with Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber died in early 1934. At his memorial service, Bosch orchestrated an “act of demonstrative non-compliance” [Margiz Szöllösi-Janze]. Under the definitions of Nazi racial ideology, Haber was considered to be of non-Aryan descent. As such, the regime explicitly expressed its disapproval of anyone attending his memorial service. However, Bosch not only personally attended the service, he also ordered the managers from I.G. Farben to join him.

Carl Bosch’s motives

This raises the question of Bosch’s underlying motives. His personal dismay, as he expressed in the case of Fritz Haber , certainly plays a role. Yet did he also advocate for Jewish employees and colleagues for primarily ethical and moral reasons, being fundamentally against their marginalization and expulsion as a matter of principle? Or was his position primarily driven by corporate self-interest? After all, Bosch was well aware of the detriment caused by the expulsion of expertise as a result of antisemitic thinking and which threatened to hurt not only his own company, but also German science and research as a whole. It is difficult to provide a conclusive answer. Much of the information is based on hearsay and often lacking additional corroborating sources. What is evident, however, is that Bosch's support was confined to individuals within his immediate circle and sphere of influence. As far as we know, they were exclusively all high-ranking scientists or employees from his own company.

Persona non grata for the regime

Bosch risked his standing by advocating for the freedom of science and research and for Jewish scientists. Toward the end of his life, he was declared a persona non grata by the governing authorities. He completely discredited himself in their eyes in May 1939 when, under the influence of alcohol, he delivered a speech in which he made pointed criticisms of science and research grounded in ideological and racist beliefs.

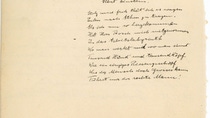

Carl Bosch and Albert Einstein

Carl Bosch was an enthusiastic amateur astronomer and had a first small private observatory built on the grounds of his Heidelberg villa in 1919. At the end of the same year, an associate of Albert Einstein initiated a completely different kind of observatory with an appeal for donations from the German business community. A tower telescope was to be built in Potsdam, later known as the Einstein Tower, to enable further experimental confirmation of the theory of relativity of its name giver. Carl Bosch did not miss the opportunity to support this project with considerable private funds and donations from BASF.

This connection is likely the reason why Bosch invited Albert Einstein to give two one-hour lectures on the theory of relativity to academics from I.G. Farben at the Ludwigshafen Gesellschaftshaus (BASF restaurant) canteen on March 1 and 2 March, 1926. On this occasion, Albert Einstein also visited the Ludwigshafen and Oppau sites. He recorded his impressions in his entry in the Bosch villafamily's private guest book. The latter is lost, only Albert Einstein's verses have been preserved as a fragment.

The lines read in translation:

Proudly and gladly would I dare

to carry owls to Athens.

When I came here like this

Mr. Bosch took me with him

into the labyrinth of work

where one thinks and where one ponders

a thousand hands and a thousand heads

like a single giant creature.

What great things man can do

if only the right man leads!

Carl Bosch as file creator?

Even though Carl Bosch himself thought little of organized record keeping, he encouraged the creation of the first BASF chronicle and had the necessary documents compiled. Today, they form a valuable source of information detailing company history.