Media

Eco friendly furniture design

Furniture classics: Good and sustainable design

There are many reasons why certain pieces of furniture become design icons and are passed down from generation to generation. But what exactly distinguishes good design? And how does the growing demand for resource conservation and a circular economy influence these timeless classics, whose durability makes them inherently sustainable?

Key points at a glance:

-

Design classics are characterized, among other things, by aesthetics and high-quality materials, making them durable and appealing.

-

The growing demand for sustainability is influencing furniture design and production processes.

-

Customers no longer just want to purchase items; they increasingly expect stories and values behind the products.

-

Design classics are evolving, even iconic furniture can change over time.

How to create the classics of tomorrow?

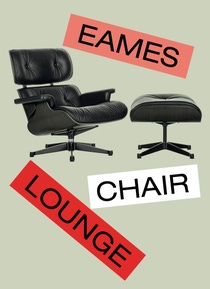

Having a piece of furniture described as “timeless” is an accolade many designers dream of receiving. But creating an object that will inspire people in the distant future is no easy task. It is certainly possible, as shown by the design classics that have already achieved this: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s elegant “Barcelona Chair,” for example, which doesn’t look like it will soon be 100 years old. Or the “Lounge Chair” by Charles and Ray Eames, the American designer couple who gave the prototype of this chair to their friend Billy Wilder in 1956, so that the director could comfortably take a break from the Hollywood bustle. Or the sculptural “Egg Chair,” with which Danish designer Arne Jacobson catapulted the traditional wing chair into the space age in 1958. Even people who know little about furniture design can recognize these classics by their silhouettes. These chairs are all still in production today, defying trends and fashions. Not only that their owners often pass such objects down to future generations. But what defines a design as a classic? Does that mean it can’t be changed at all? Or can it also be impacted by the new demand for sustainability and a circular economy? And conversely, what does it mean for designers and manufacturers that for it to be long-lasting, the sustainable furniture they create today must also be timeless – perhaps to become a classic itself one day?

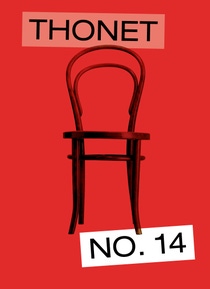

One person who accomplished this was the cabinetmaker Michael Thonet. When he and his sons began bending beech wood with steam in 1850s Vienna to craft a lightweight, stable, and even affordable café chair, it never crossed anyone’s mind that what the Thonets had created would become the archetype of all furniture classics. But their chair “No. 14” met all the criteria by which we still measure good design: aesthetics that immediately please the eye; a design that attests to high functionality and impresses by dispensing with any ornamentation – less is more! And finally: high-quality materials and a perfectly handcrafted finish. Of course, designers have only limited influence over whether future generations will embrace an object and elevate it to classic status. As German celebrity designer Konstantin Grcic has noted, a designer can only aspire to “design things that have quality, that function but also have a beauty that leads to a relationship with the object. This creates the feeling that you want to live with things for a long time, take care of them and maybe even repair them. These are all tasks that we have to fulfill.”

Furniture design – then and now

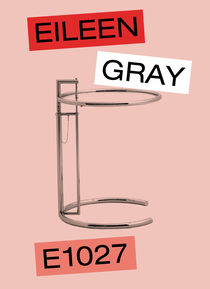

Beauty, durability, functionality – these qualities also distinguish the furniture icons from the heyday of Classic Modernism after World War I. For example, the elegant chrome and glass table “E1027,” created by Irish designer Eileen Gray in 1927. Or Le Corbusier’s fur-covered chaise longue “LC4” from 1928. Other examples include pieces designed by Mart Stam, Marcel Breuer and Wilhelm Wagenfeld for mass production in the reformist Bauhaus spirit of the 1920s. But the steel tube chairs, innovative lamps and storage systems created by these and other designers for small apartments were ultimately produced only in small quantities – and even then, they were too expensive for many people to buy. Mass production only became a reality with the emergence of furniture discount stores in the 1960s. As a consequence, neither the manufacturers nor the buyers placed much value on the quality or durability of furniture that seemed inexpensive but was ultimately just cheap. That is why there are few classics in this segment. Something that doesn’t last long can’t become a design icon. A bizarre exception, of which there are a few: the “Throw-Away” sofa from 1965, which already carried the intended disposability in its name. The block seat consisted of foam with a vinyl cover and was promoted as a consumable item, as there was still limited awareness about wasting resources at that time. In a twist of design history, this sofa – as a brand-new luxury model with textile or leather upholstery that is actually replaceable, and as a vintage collector’s item (since some originals have apparently survived) – is selling for thousands of euros or dollars today.

And now? To become a hit, furniture needs to excel in more than just aesthetics, functionality and material quality. “Sustainability and the circular economy have become a given,” says someone who should know: Christian Grosen, Chief Design Officer of the Swiss company Vitra, one of the most distinctive designer furniture producers in the world. “Business and retail customers are increasingly interested in what they are buying – for example, a product’s contents or the story behind it. More often now, they also want a narrative, a statement, and not just a piece of furniture. So, it’s just a question of time until every individual and every company is forced to act sustainably and within the circular economy, because this is what customers expect.”

The true value of materials and eco-conscious design

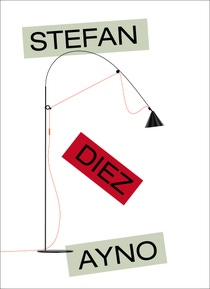

The changing demands, placed not only on the product but also on the conditions under which it was created, also present new challenges for designers. Transparency is key – as in the case of “AYNO,” a minimalist luminaire, which German designer Stefan Diez conceived a few years ago for the long-established manufacturer Midgard. The luminaire is made of mostly recycled materials, requires no tools for installation or removal by its owner, won’t pose any problems during electrical repairs, and can be disassembled into pre-sorted components for recycling after use. The manufacturer also states that the materials are sourced locally so that transportation and logistics leave only a small footprint.

The designer Nathan Yong from Singapore, who is known for sculptural chairs and sofas that appear to float in space, also sees the desire for transparency as a driving force. For his “Lifecycles” collection – a series of seating furniture and tables made of cherry, maple and oak – he performed a lifecycle analysis of each design’s environmental footprint so as to draw buyers’ attention to the object’s sustainability. “When people consume something, they don’t always appreciate the true value of the object,” says the multiple award-winning designer about his approach. “I want these artistic works to enable them to question the true value of the objects for themselves, for nature, the community and the well-being of the planet.”

Design classics are never completely finished but are constantly evolving.“

Designing for tomorrow: Sustainable and innovative

These days, Vitra is even working with recycled materials, although Chief Design Officer Grosen notes that it takes time “to develop good aesthetics with sustainable materials.” For example, when the company started to manufacture variants of the “Eames Plastic Chair” – another 1950s design by Charles and Ray Eames – using remanufactured polypropylene, there was a problem: “The seat shells have tiny pigment marks throughout due to the recycled material,” so the appearance of the classic chair has changed. How do customers respond? They don’t care, says Grosen: “Nowadays, they accept the material’s natural characteristics.” In any case, even with classic designs – of which Vitra’s portfolio contains an impressive number – Grosen believes that “they are never completely finished but are constantly evolving. Some of our products have been on the market for more than seven decades and have undergone numerous updates and improvements.” Another example of how classics move with the times: The dimensions of the “Eames Lounge Chair” described above have grown by several centimeters because people are bigger today than in the 1950s. By 1988, the typical Rio palisander for the plywood shells had already been replaced with Santos palisander, which is not an endangered wood species. And the soft polyurethane foam in the upholstery, which is made by BASF, is the first mechanically recyclable PU foam to be used in a Vitra product.

We’ve now come full circle. Even big-name designers will likely not argue with the need to continue updating their designs in keeping with the spirit of the times. Charles Eames saw the role of a designer as that of a “very good, thoughtful host, anticipating the needs of his guests.” He and his wife Ray obviously hit the nail on the head.

Related links

Photos: © Thonet Nr. 14 by Michael Thonet/Thonet GmbH, © Wishbone Chair by Hans J. Wegener/courtesy of DWR; © Tulip Armchair by Eero Saarinen/courtesy of Knoll/Federico Cedrone; © Wassily Lounge Chair by Marcel Breuer/courtesy of Knoll; © PH-5 von Louis Poulsen/courtesy of Louis Poulsen; © Lifecycles by Nathan Yong; © Adjustable Table E1027 by Eilleen Gray/classicon.com; © AYNO by Stefan Diez/Midgard; © Lounge Chair by Charles & Ray Eames/Vitra