Media

Epidemiology of malaria: challenges and innovations

Fighting malaria: "We can do this"

Malaria cases worldwide have not declined as many hoped. In some areas, they are even increasing. Still, expert Justin McBeath remains optimistic.

At a glance:

-

Vaccines alone are not enough to defeat malaria. A combination of vaccinations, insecticides, medications, and diagnostic methods is needed to effectively combat the disease.

-

Despite the rising number of malaria cases due to resistance, financial constraints, and the COVID-19 pandemic, there are positive developments, such as new insecticides, that offer hope.

-

Justin McBeath is convinced that malaria can be defeated and emphasizes the importance of evidence-based measures and international cooperation.

Years of battling a persistent pathogen

According to the World Health Organization, there were almost 263 million malaria cases in 2023 – an increase of 11 million on the previous year – and nearly 600,000 deaths. Although insecticide treated nets and insecticides have had huge impact in tackling the disease, one reason malaria is proving so difficult to control is that the Anopheles mosquito, which transmits malaria, is extremely adaptable.

Justin McBeath, CEO of the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC), has spent 25 years in the fight against malaria. The U.K. national explains the challenges and opportunities, and what keeps him motivated in the ongoing battle to eliminate the disease.

New malaria vaccines as possible game changer

Two malaria vaccines for children were approved in 2023, and others are currently being developed. Does this mean the fight against malaria is over?

The current suite of malaria vaccines is going to play a really important role in reducing the number of deaths from the disease, but the vaccines don’t prevent malaria transmission and its other effects. So there is a continued need for other tools. The concept of an integrated approach – different tools being deployed together – is really important, as these vaccines are not silver bullets. If we get to a point where there’s an effective transmission-blocking vaccine, then that might significantly change the dynamic. But that’s likely to be some time away.

So it’s not a case of vaccines taking the place of insecticides – we’ll always need both?

Ultimately, they’re complementary. Countries need the availability of a toolbox of effective options, also including drugs and diagnostics, and they need funding support to deploy a mix of locally appropriate tools. We therefore need data and evidence to support where, when, and how they should be deployed alongside each other. And that’s all in a resource constrained environment. It’s really important for there to be a range of tools for countries to choose from to match their needs.

What are the most effective preventive measures?

Of the reduction in malaria prevalence that occurred between 2000 and 2015, 78 percent was attributable to insecticide-based interventions – nets and indoor residual spraying (IRS). The biggest part of that was insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITN), so it’s likely that trend will continue. But it’s not a static situation. There are dynamics to take into account – resistance, outdoor transmission, drug resistance, climate change and others. The situation with resistance is evolving, so having some new modes of action on nets is going to be extremely important in maintaining effectiveness. But nets and IRS don’t address all the challenges of outdoor transmission, so other tools are also going to be needed.

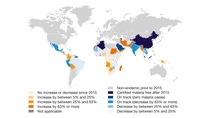

On track? Global malaria spread

*GTS: Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030; Source: WHO estimates 2024

Challenges of recent years

After years of progress in tackling malaria, infection rates are on the rise again. Why is this?

It’s partly a legacy of covid-19 and the disruption to countries’ health systems when resources were diverted, then there is the pervading challenge of resistance to drugs and insecticides as well as the ever present issue of funding constraints and ability to reach coverage targets. There will always be funding constraints. They limit what tools and interventions malaria programs can procure.

How do you see the situation developing over the next few years?

I think there are going to be continued challenges, at least in the area of vector control. There are some positives in terms of new insecticides, which are likely to become available in the next five years – innovations that should help with addressing the resistance challenges, but we are operating in a biological environment – things are never static. The availability of vaccines also creates questions of how to generate the necessary data to support decision making when there are more tools available. But that’s not such a bad challenge to have.

Is the international community committed to fighting malaria?

All the organizations we engage with, whether it’s the country programs, the WHO or the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, are doing a fantastic job and are fully committed. But malaria is one health challenge among many – there are also massive challenges with tuberculosis and HIV, and of course the Global Fund finances the fight against all three. For them, prioritizing resources across three diseases is a high-level challenge before we even get into the nitty-gritty of malaria itself.

How likely is climate change to push the disease into new regions?

Rainfall, temperature and mosquitoes go hand in hand. For example, there was a rapid upsurge in malaria cases following devastating floods in Pakistan in 2022. With climate change, there’s some logic to say where it gets warmer and there’s greater capacity for mosquitoes to breed that’s likely to increase the threat. But only if malaria is already spread in the population, because the mosquitos are the vector, not the origin of the disease. That’s why a growing mosquito population doesn’t necessarily mean more disease.

Countries need effective options and funding to deploy a mix of locally appropriate tools.“

Essential in the fight against malaria: determination and optimism

You’ve been working in this field for 25 years – what inspired you to focus on malaria?

I’m fundamentally a biologist by training, by education, by interest. Even as a kid I was into bugs and animals and spent a lot of my time outside. I’ve always had a fascination with tropical diseases, alongside a personal belief in doing something that leaves the world in a better place. At university I was inspired by a lecturer who presented his work on an onchocerciasis ("river blindness") program in West Africa. It convinced me that I wanted to do something like that – a mix of science, tropical disease and helping people. And then, when I did my M.A., I had the opportunity to work in West Africa as part of my research on insecticide-treated mosquito nets. I saw the impact the nets were having.

When do you think malaria might finally be eliminated?

We’re seeing a slow but steady increase in the number of countries where malaria elimination has been achieved. Some of those are smaller countries, which makes it easier, but I personally would see it to be a significant achievement if by 2040 the map could be constricted to just a handful of major-burden countries. There are still massive-challenge countries like Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo or some of the central African countries. It’s encouraging that there’s progress being made each year. But the only way we’re going to get there is by using that range of different tools, deploying them in a way that’s evidence-based, and with resource and investment behind them.

Working in this field must be harrowing at times. What motivates you to keep going on a day-today basis?

I’ve never not been motivated. I certainly believe that we will ultimately achieve elimination of malaria – you’ve got to hold on to that. As a CEO I have a responsibility for the motivation of our employees, who are equally committed and passionate. And I really do fundamentally believe that we can do this.

JUSTIN MCBEATH

joined the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC) as CEO in 2023. IVCC is a not-for-profit, public-private partnership working together with industry, the public sector and academia to facilitate the development of novel public health insecticides against insect-borne diseases. McBeath worked in various international leadership positions related to the development, registration and marketing of mosquito and other pest management solutions. He holds a bachelor’s degree in agricultural zoology and a master’s in medical entomology.

Read more

Life-saving nets

When cases of malaria increased around the world – due largely to mosquitoes’ resistance to common insecticides – BASF developed the Interceptor® G2 (IG2) insecticide-treated mosquito net. IG2 kills resistant mosquitoes using chlorfenapyr, a new class of insecticides for public health. With support from partners like the Gates Foundation and MedAccess, over 100 million IG2 nets were delivered to malaria-affected countries in 2024. BASF is currently innovating to develop next generation Interceptor nets.