800 million

people are overweight

Media

If a time traveler from the 1950s landed in a Western supermarket today, they wouldn’t believe their eyes. Asparagus, cherries and pears, available all year round; microwaveable burgers here, a whole aisle of breakfast cereals there. It looks impressive, but this abundance comes at a cost.

Many experts agree that our current food system is not fit for purpose. After all, we live in a world where almost 800 million people are obese while a similar number – 821 million – still go hungry. Poor diets are linked to malnutrition and disease, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), no country is unaffected. In the European Union, depending on the country, 30 to 70 percent of adults count as overweight, and obesity affects 10 to 30 percent.

800 million

people are overweight

821 million

people are still chronically undernourished

25 percent

of emissions are caused by our food system

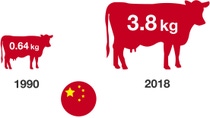

Our diets are damaging not just our own health but also that of our planet. A 2012 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) report observed that we are living as if we had an extra planet at our disposal, and at this rate, by 2030 even an extra two planets wouldn’t be enough. Just take our consumption of beef. It is an everyday food for a growing number of people, but it requires 20 times more land and results in 20 times more greenhouse gas emissions per unit of protein than beans or lentils.

As Western-style diets become more popular in rapidly developing countries, demand for meat is growing. Tim Searchinger, Senior Fellow at the World Resources Institute in Washington D.C., USA, draws the conclusion that “the people who eat large amounts of beef and lamb today have to hold down their consumption, making it possible to produce enough meat so that others can eat a little more.” In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, many people could benefit from the protein and iron gained through eating more meat.

Recent trends suggest there is actually a growing awareness, particularly among young urban consumers, that we need to eat less meat. There has been a rise in “flexitarians” – people who have a primarily vegetarian diet but occasionally eat meat or fish. A survey in the United Kingdom found that 14 percent of the British identify as flexitarian. The U.K. has also embraced veganism: in 2018, 16 percent of all new food product launches were vegan, more than in any other country. Variations on Meat-free Monday have spread to more than 40 countries in the past 10 years.

The food industry has moved fast to meet the growing demand for meat and dairy substitutes with innovative products. Nondairy milk has become mainstream, with a wide variety of alternatives offered, and food technicians are working hard on making the soy protein-based burger as close as possible to the experience of eating a beef burger. It is the soy leghemoglobin, which contains the iron-rich molecule heme, that gives these burgers their meaty flavor. Meanwhile, efforts are underway to bring lab-grown meat to the market and one company is working on lab-grown chicken nuggets. Others are developing artificial fish fingers.

Do these trends have a positive net impact? Possibly, but as Michael Siegrist, Professor of Consumer Behavior at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, points out, eating soy or tofu on top of an otherwise unsustainable diet will not improve matters. “We don’t know whether people are reducing their meat consumption by substituting beef with these new products, or eating these new products in addition to meat,” he says. And not every new health product is more sustainable. Almond milk, for example, a popular type of non-dairy milk, is derived from a very water-intensive crop.

Food choices depend on many factors – wealth, culture, availability and personal taste. There is no one-size-fits-all diet that is healthy and sustainable for everyone in the world. Perhaps one answer for people in countries where more choice exists lies in making recommendations that are more specifically aimed at the individual.

According to recent research by Rabobank, a Dutch financial services company and a global leader in food and agriculture financing and sustainability-oriented banking, personalized nutrition is set to become a game-changer. The growing ability to link health issues to physical attributes such as genes or gut bacteria makes this possible. With 3D printing technology added, it is now possible to provide food based on specific, personal nutritional needs, whether it’s for athletes or people with medical issues.

For the wider population, the value of personalized nutrition could be that it opens up a new, more compelling route to a healthy, sustainable diet. “Personalized enough meat so that others can eat a little more.” In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, many people could benefit from the protein and iron gained through eating more meat.

Personalized nutrition is all about measuring, intervening and supporting a behavior change.”

Fitness or diet apps already help users optimize caloric intake and nutrients. But more specialized products and services are emerging, such as BASF’s Omega-3 Index testing kit. The kit uses dried blood spot technology to accurately measure omega-3 fatty acids levels. These have been proven to have many health benefits, including reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease. With this information, consumers can adjust their intake and monitor results to ensure that any dietary changes are helping.

Conventional wisdom about eating more vegetables and fewer hot dogs will always be true. Everyone knows it. Recent diet trends and product innovations are encouraging, but we need a big toolbox if we are going to change global diets. As Scheffler suggests, maybe personalized nutrition data will be more effective in triggering behavior change than the comparatively blunt tool of global diet recommendations, and will contribute to a much-needed recalibration of diets.

“If you stick to what you really require, you will consume far less, and that would make these calories available for others,” says Scheffler. “We need to produce the right things for the right people. There’s an environmental aspect to that, but also the social benefit of reducing the cost of health by focusing on better nutrition and having people who can live longer, active lives.”

Of course, what we eat is only half the story. The other half is about how we produce food. In the next section, we find out how agriculture is changing to meet current challenges.

The healthiest diets are those that have the deepest roots in history and tradition.”

Food is an emotive subject. It plays a central role in our social lives and culture, so changing diets is not easy. Sara Roversi’s organization recognizes this, while working to improve sustainability in the global food ecosystem. We ask her how we can improve our diets and still enjoy what we eat.

We are not driven by what is right but by pleasure and by our own past, so it’s tough to change behavior. Think about the occasions when people come together, at big sporting events for example, and how much unhealthy food you find there like hot dogs, hamburgers, and soda.Yet these are occasions where people are having a good time, sharing positive emotions with relatives and friends, so the connection with unhealthy food is tied with some of their most positive experiences in life. That is why we are working with sponsors to make them aware of the damage they are causing, maybe without realizing it.

It’s not just knowledge, it’s also about mindset. Over the last decade, everything has been focused on shape and efficiency, on creating the perfect, round tomato without considering its flavor or juiciness. What if tomorrow we started evaluating whether a product is good or not based only on its taste? If you work backward from there, the soil and production methods will be different, and distribution chains will be shorter.

When we talk about the Mediterranean diet we are not just talking about ingredients, but also aboutculture – how you share meals and when you eat them. Food is a crucial part of human identity. It’s part of our DNA. The healthiest diets are those that have the deepest roots in history and tradition. In the past, food was more connected with health, because food was the starting point for medicine, so traditional diets are healthier in origin. That’s why I don’t think the right approach is to say that everyone should adopt a Mediterranean diet withoutconsidering the context. What matters is that we should eat food that is good for us, good for the planet and in balance with the culture of the place where we live.

Tap to explore