The value of waste

Throwing away is a thing of the past. In the future, we will think only in cycles. The intelligent reuse of waste as a raw material still holds enormous untapped potential.

Tom Szaky’s path to the global stage began knee-deep in waste. Szaky, 38, still shudders when he thinks about his first wasterecycling company. However, even then this company founder already had a clear idea of the vision that he would present some two decades later, in 2017, from a podium at the World Economic Forum in Davos – the idea of abolishing waste. After all, in nature there is no waste – only raw materials.

Szaky’s company, TerraCycle, now processes even difficult waste, such as cigarette butts, into plastic pellets. Recently, this waste pioneer has even been trying to use his new deposit system start-up to completely banish disposable packaging.

New life for waste

Fast-growing mountains of waste

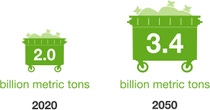

The fact that an enfant terrible of the waste sector, such as Szaky, and those who hold power in business and politics are coming together is the result of a problem that, in view of its huge dimensions, also demands unconventional solutions. According to the World Bank, humans annually produce around 2 billion metric tons of waste. The development bank estimates that this figure will rise by about 70 percent by 2050, to some 3.4 billion metric tons.

The biggest challenge is plastic: 242 million metric tons of plastic waste – approximately – is produced each year according to the World Bank. That equals 12 percent of the total amount of all waste. Politicians are accordingly applying pressure. In May 2019, the European Union (E.U.) passed a law that will ban disposable plastics such as straws or plastic cutlery from 2021. This strong measure is in line with the action plan for closing the loop that the E.U. launched a few years ago. For some time now, the thinking of government and business leaders has revolved to a large extent around the three Rs of Reduce, Reuse and Recycle – and that principle is increasingly gathering pace.

Ending plastic waste in the environment is a challenge we can overcome.”

Companies including BASF have recognized both the signs of the times and the value of acting together. In January 2019, nearly 30 companies launched the global Alliance to End Plastic Waste (AEPW), and the number of members is growing. With $1 billion pledged, this not-for-profit initiative is promoting new solutions for minimizing the impact of plastic waste on the environment, improving processes in the waste-management business, and putting that plastic back into circulation. Partnerships for this purpose are also being formed with local organizations. “Ending plastic waste in the environment is a challenge we can overcome through sustained effort, collaboration and a commitment to innovative solutions,” says Jacob Duer, president and CEO of the AEPW and former program director at the United Nations Environment Programme.

BASF is working on contributing toward closing loops in plastics with a new raw material. ChemCycling™ is the name of the project under which the company is using recycled pyrolysis oil from discarded plastics as a raw material in production and thus replacing some fossil raw materials. BASF’s partner companies heat various types of plastic waste to temperatures between 300 and 700 degrees Celsius in an oxygen-free environment. The long polymer chains in the plastics are dissolved in the heat and become pyrolysis oil in shorter chains and then gas in very short chains. This gas is used to heat the process. “This means that a large proportion of the energy required comes from the plastic itself,” explains BASF sustainability expert Andreas Kicherer, PhD, in Ludwigshafen, Germany. The remaining liquid part can now be cleaned and processed before being fed into BASF’s steam cracker. There, the oil is again broken down into its basic components so that new products, including plastics, can be produced from them. In July 2019, BASF unveiled product prototypes from the pilot phase, such as vehicle parts and cheese packaging based on chemically recycled materials. “In the past, people would have said that you could never use recycled plastics in safety- related components or in contact with foodstuffs, but we have now proven that this does work,” Kicherer says. “ChemCycling has the great advantage that we are able, for the first time, to achieve the quality of completely new goods.

However, it has the additional benefit that we can declare that the item was made from recycled raw materials.” This works in practice through a certified mass balance process, under which the proportion of recycled material used at the start of production is mathematically assigned to the finished product. Viewed in isolation, Kicherer explains, pure production with raw oil will probably often be cheaper, but the resources and CO₂ saved have to be taken into consideration, as the recycled plastic waste would otherwise be processed into less sophisticated products or simply burned. However, before it is possible to use ChemCycling on a large scale, there are technological requirements to meet and regulatory barriers to overcome.

Does it make sense to recycle CO2?

When products are made or energy is generated, the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide is often created. Instead of just being blown out into the air, it could also be used as a raw material. In theory this is possible, but there are limits to the idea.

Using CO2 to make diapers highly absorbent may sound like an unusual idea, but for researchers it is already in the realm of the possible. For instance, BASF is working on using carbon dioxide in conjunction with ethylene to produce sodium acrylate, an important source material for superabsorbents that does its job in diapers and other hygiene products. This is just one example among many. All over the world, companies are working on taking the chemical compound composed of one carbon and two oxygen atoms and using it to make new products, such as rigid foam or intermediates for fibers. The problem is that the carbon dioxide molecule is so inert that it takes a huge amount of energy input to get it to react with other molecules.

“After nine years of research, we achieved it for sodium acrylate. At first, the process was very complex and liable to break down – and very expensive,” says Rocco Paciello, PhD, who leads a research group for homogeneous catalysis at BASF. Furthermore, in reactions on a large scale between the gaseous compounds of CO2 and ethylene, there are many interdependent parameters to deal with. “If you change one parameter, this will automatically influence all the others, too. Six months ago, I would have regarded the speed of the reaction as our greatest challenge,” Paciello says. However, he continues, that is now good enough with the help of a suitable catalyst. “At present, our main problem is the excessively high energy consumption in the reprocessing of the reaction mixture.” This is because the process can be economically viable only if it is possible to reduce the energy input. Only then will the lower raw materials costs compared with traditional production processes actually pay off.

Impact on climate change? Modest

In the foreseeable future, CO2 is not expected to have any more than a niche existence as a raw material. At BASF, CO2 is meanwhile being used constantly as a raw material in the production of sodium acrylate on laboratory scale. It will take some more time before this will also work on an industrial scale. “We could get there in about five years,” Paciello hopes.

However, it is also clear that the impact that even extensive use of CO2 as a raw material in the chemical industry would have on climate change would be only very small. For BASF, therefore, the emphasis in terms of the switch to climate-friendly production is on avoiding CO2 emissions. The company is targeting CO2-neutral growth by 2030. In addition, BASF is conducting research into new production technologies that aim to reduce CO2 emissions further or avoid them completely. The focus here is on basic chemicals, which are alone responsible for about 70 percent of CO2 emissions in the chemical industry. In addition to new processes, work is in progress on how to use more energy from renewable sources in the future. For example, BASF is conducting research into ideas including an electric heating concept for steam crackers, which crack crude petroleum at a temperature of 850 degrees Celsius. If this temperature could be achieved with renewable electricity, instead of the natural gas that is used at present, CO2 emissions could be reduced by up to 90 percent.

Facts about carbon dioxide

Facts about carbon dioxide CO₂ is a natural, non-toxic by-product of the breathing of many living creatures, and is also released when wood, coal, oil or gas are burned. It has a very small concentration in the air, at only 0.04 percent. However, it plays a big part as a greenhouse gas. CO₂ absorbs a proportion of the heat given off by the Earth into space and reflects it back.

Revamping electronic waste

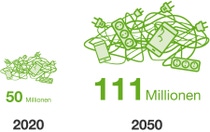

Buried treasure lying dormant in electronic devices rather than in complex chemical processes is the domain of the scientist Rüdiger Kühr, PhD. He is conducting research at the United Nations University (UNU), which is headquartered in Japan and has taken up the cause of reducing electronic scrap worldwide through its E-Waste Coalition. Almost 50 million metric tons of electrical and electronic devices are discarded every year and, according to U.N. calculations, this figure could rise to 111 million metric tons a year by 2050 – if nothing is done.

In that event, there will be a danger of serious distortions with regard both to disposal and to efforts to ensure that the electronics industry is supplied with raw materials such as rare-earth elements, Kühr warns. Kühr, who is director of the Sustainable Cycles Programme at the UNU, demands nothing less than a 180-degree turnaround in the production and use of electronic devices – away from disposable electronics and toward recycling and reuse. “The responsibility here rests with producers,” he says. They need to focus their innovative energies not on quick switches to increasingly trendy models, but on how to get easier access to components, how to repair and recycle electronic equipment better, and how to increase its service life across the board.

Rethinking waste around the world

Avoiding waste, reusing things, making them smart – we look at some pioneering places.

This is where new thinking about digitalization, in the spirit of sharing is the new owning, could play into the electronics industry’s hands. According to the World Economic Forum report, A New Circular Vision for Electronics, new technologies from the Internet of Things to cloud computing hold huge potential for better product tracking, recall andrecycling. Using rather than owning – already common practice in the leasing of photocopiers by companies – is a principle Kühr believes points the way to the future for smartphones, tablets and the like. Kühr talks about dematerialization here. This means that the manufacturer remains the owner of the device, with a vital business interest in offering consumers the best possible service.

The intellectual resources for such circular thinking are something that electronics manufacturers, which are mainly from Asia, could probably find on their own doorstep. In his book, Decoding China, the author Diego Gilardoni points out that Western observers look at things in their own right, whereas Chinese people focus on “relationships between things.” This predisposes the country to the idea of doing business without waste. “Perhaps it is because of this thinking in terms of connections, which never loses sight of the future, that this Asian country already has such impressive examples of a circular economy,” says the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, whose China expert, Vigil Yangjinqi Yu, has collected case studies to support this. For example, the Beijing startup YCloset has declared war on throwaway clothes. For a fixed monthly payment, fashion-conscious Chinese women can hire and return up to 30 items of clothing, ranging from business suits to party outfits – all organized through a smartphone app. This is just one contribution toward curbing theextremely water-intensive and often environment-unfriendly production of more and more new, cheap-fashion collections.

Buyers are prepared to pay even a high deposit if the service is right.”

The idea of smart use and reuse, rather than short-lived ownership and disposal, is also the business model for Tom Szaky’s newly established company, Loop. When it took its first steps in the USA, Szaky made an astonishing observation, which is also a sign of a long-term change in the mindset of consumers: buyers are prepared to pay a high deposit for a product, if the accompanying service is right. “This not only makes circular economy functional, but we now have the ability to make products that are sustainable, beautifully designed and of high quality,” he says.

Three waste tacklers

Waste mountains are growing and growing. But so is the number of people who are not prepared to accept this. Here are three of them.

The waste banisher

Bea Johnson, blogger, San Francisco, USA

The almost waste-free lifestyle of Bea Johnson is manifested in a preserving jar. It contains her family’s entire waste output for a year. Is there a garbage can in the house? No – not needed. Johnson leads a zero-waste life. She banishes waste-intensive products and limits herself to the bare essentials. This waste avoider turns all her bed linen into cloth bags, which she uses to do shopping that as a rule consists solely of unpackaged goods. Her everyday items are almost all secondhand. The same applies to her wardrobe, which has so few garments that everything fits into one small suitcase. “However, it would be a mistake to think that we have to do without because of this,” Johnson says, emphasizing the gains in quality of life. She enjoys working out that she also saves money – about 40 percent compared to before. Since she started blogging about her zero-waste lifestyle in 2009, the movement has grown rapidly. This waste activist now has more than 400,000 followers on social media.

The waste reverser

Geert Bergsma, scientist, Delft, Netherlands

Geert Bergsma is “a little surprised” to find that his area of research is so suddenly attracting attention. He says, slightly in amazement, that everybody has started talking overnight about the global threat from plastic waste. “This is helpful to get more attention for the recycling of plastics,” says the expert at research organization and consultancy CE Delft. For a number of years, the 53-year-old Dutchman has studied the environmental benefits of an innovative solution to the problem of chemical recycling. He discovered that a particularly promising answer is depolymerization, where plastics are turned back into their original constituent parts with only a few chemical steps. “This process can cope with a lot of pollutants,” Bergsma explains, “and makes possible a true circular economy in the case of packaging.” In this way, a drink bottle can remain a drink bottle rather than become a lowerquality material – which would, ultimately, mean waste. “It also saves the largest amount of CO₂, similar to that of mechanical recycling and better than feedstock chemical recycling,” Bergsma stresses. The calm, persevering work of scientists like him seems to be bearing fruit. A new factory employing depolymerization is now being created in the south of the Netherlands. Here is Bergsma’s vision: “Mechanical and chemical recycling together could spell the end for the incineration of most plastic waste.”

The waste rethinker

Tom Szaky, entrepreneur, Princeton/USA

It all started with worms. Tom Szaky, then a student, fed them leftovers from the Princeton University canteen and made their feces into fertilizer. The retail giant Walmart took an interest in it, and this natural fertilizer became part of its range. That was in 2007. Now, more than 200 million people are collecting their waste for TerraCycle, the company set up by the waste pioneer from New Jersey.

What sustainability pioneer Szaky wants is nothing less than the abolition of waste. His company, with branches in 21 countries, is considered a pioneer in recycling the non-recyclable, and it does things like turning chewing gum into polymers for frisbees or diapers into park benches. However, even Szaky can see that the problem of waste cannot be solved by recycling alone. Less waste has to be produced in the first place. Szaky, 37, set up Loop, a zero-waste purchasing platform that aims to abolish disposable products by means of a global circular system for packaging. Major companies such as Carrefour, Procter & Gamble, Unilever, Nestlé and Mars are on board. Together, they have designed new, long-lasting, returnable packaging for some 300 products offered through the platform, ranging from ice-cream cartons that can be refilled again and again to packaging for stick deodorants that can be repeatedly used. “In essence, Loop is a reinvention of the 1950s milkman – then as now, products are delivered to your door in reusable packaging, and once they have been used, they are collected, cleaned and refilled,” Szaky says. Loop started its pilot phase in Paris and New York in May. The next step is to expand into parts of North America and the United Kingdom. Canada, Germany, and Japan are due to follow.