From the ground up

The soil beneath our feet is the world’s largest terrestrial carbon store. Pioneering farmers and agronomists are working on methods to harness its potential. Their insight: Climate protection and a rewarding harvest can go hand in hand.

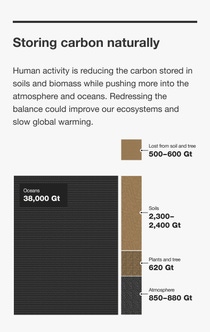

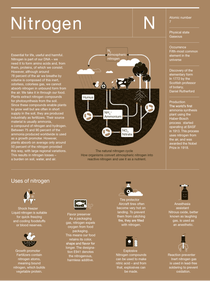

The soils of the world contain more carbon than its forests, woodlands and atmosphere combined,” says Professor Rattan Lal. Agriculture, by replacing forests with fields, has been depleting that vast carbon store since its birth 10,000 years ago, so “we should see recarbonization of the soil as an essential part of the solution to climate change.”

Lal, Distinguished Professor of Soil Science at Ohio State University, United States, stresses that agriculture must become nature-positive. “That means producing more from less: focusing on the efficiency of inputs, rather than the rate.” Too many agricultural systems, he explains, rely on very high volumes of fertilizers and other chemical inputs to achieve their current yields. The alternative regenerative agriculture techniques he espouses are deceptively simple: minimizing tillage, replacing flood irrigation with more water-efficient drip approaches, and using cover crops and agricultural residues to boost nutrients.

Professor Rattan Lal has spent 60 years unlocking the secrets of soils and devising farming methods that can improve them.

“And we should use less of the land itself,” he adds. Reducing demand for agricultural products through more efficient utilization and dietary changes would allow more land to be returned to nature, capturing billions of tons of carbon.

In some parts of the world, large-scale efforts to protect the soil are already under way. China’s Three-North Shelter Forest Program, known as the Great Green Wall, is the world’s largest human-made forest. Upon completion in the 2050s, it will span 4,500 kilometers, slowing the southward advance of the Gobi Desert. However, most places don’t have the political, social or economic structures that permit such sweeping changes to land use. The health of their soils depends upon the choices made by millions of individual farmers. That might just be the best place for the next green revolution to begin.

Old trees, new life

Tony Rinaudo, an Australian agronomist, has spent his career helping farmers in the Global South to adopt more sustainable practices. His work began in Niger, West Africa, in the early 1980s. “It was a landscape on the verge of ecological collapse,” he says. Deforestation had stripped protection from the soil, water shortages were rife, and the Sahara Desert was advancing from the north. Rinaudo’s tree-planting efforts were failing, however: “80 or 90 percent of the saplings we planted died or were destroyed.”

He was about to abandon the project. “Then one day I noticed one of the low bushes next to the road, and took a closer look,” he recalls. That bush, like millions of others, turned out to be a tree, regrowing from a leftover stump. “In that instant, everything changed. We didn’t need millions of dollars to make a dent in this. We didn’t need a miracle species of tree that could withstand droughts and people pulling them up. Everything you needed was literally at your feet.”

Known as “the forest maker,” Tony Rinaudo helps farmers in Africa and beyond to protect their soils by regrowing trees from left over stumps when land is cleared.

With well-established root systems to access water and nutrients from deep in the soil, trees that regrow from stumps are much more likely to survive than new seedlings. That revelation shifted Rinaudo’s approach. He started a new project, incentivizing farmers to allow a few trees – 40 per hectare – to regrow on their land. “They thought the idea was strange, but a minority could see it was doing some good,” says Rinaudo. “A little more organic matter was going into the soil, wind speeds were slower, the temperature was lower, and some of the traditional wild foods were coming back.”

In the following years, Rinaudo’s “farmer-managed natural regeneration” approach steadily took root in Niger. “After 20 years, we had 200 million trees across 5 million hectares, without planting a single one. All from an investment of about two U.S. dollars per hectare,” he says. Mature trees each absorb about 25 kilograms of carbon from the atmosphere every year, and more is captured by the improved soils on regenerated farms.

Rinaudo and his current employer, the charity World Vision, went on to launch projects in other African countries, including Ethiopia, Ghana and Senegal. Today, farmer-managed natural regeneration is used in about 25 countries. Most common in Africa, it has also been adopted in countries such as Indonesia, Myanmar and East Timor.

Pulling the plow

Climate and environment-sensitive practices are gaining momentum in the rich world and in conventional agriculture, too. William Pitts grew up on an arable farm in Northamptonshire, England, which he now runs alongside his brother. The business grows grains on around 800 hectares. “We now manage about 10 percent of our farmland for the environment: flowers, butterflies, flora and fauna. And the rest of it we try to farm in a way that protects the soil as much as we can,” Pitts says.

William Pitts has switched from conventional plow-based agriculture to no-till techniques across his farm in England.

That desire to conserve the soil has led the Pitts to gradually abandon the plow. Today, they use direct drilling equipment that deposits seeds into a narrow slot in the surface of the soil. A strategy that once looked radical is now paying off: Yields on the Pitts’ farm are as high, and sometimes even higher, than they were, but its costs have fallen significantly. “Under our old system, we would use 120 liters of diesel per hectare across a year’s cropping cycle,” he says. “Today, we have managed to cut that down to 70 liters, which is a significant 40 percent reduction.”

The land is holding more carbon too. “Tests have shown that the organic matter content of the soil has doubled since we adopted zero-tillage techniques,” says Pitts. That’s good for the crops, but for a growing number of farmers around the world, the soil’s ability to capture more carbon from the atmosphere is also becoming a source of income.

Carbon as a crop

Kasey Bamberger is part of a family partnership that grows corn, soybeans and wheat on around 8,000 hectares of land in southwest Ohio, United States. “We’d heard a lot of discussion about climate change, but we really started to see its impact at first hand in 2018,” she recalls. “The weather patterns in our area began to change, we were seeing some topsoil loss, and experienced different weed pressures. That was the catalyst for our farm to start exploring the potential of regenerative agricultural practices like reduced tillage and planting cover crops.”

While it promises significant benefits over the long term, the transition presented extra costs and risks. “We’ve already had things go wrong,” she says. “We’ve had to cut and remove cover crops that grew too much in wet weather, for example. That’s not such a big deal on 200 hectares, but when you think about over 2,000 hectares, it makes your head spin.”

For the past two years, the business has joined a carbon offsetting scheme, which pays it for every ton of carbon added to the soil. The money comes from companies and individuals around the world, who buy carbon credits to offset their emissions. The price varies according to shifts in global carbon markets. With new practices currently adding 2 to 4 metric tons of carbon per hectare every year, those payments are a useful financial buffer. The system could benefit farmers of all scales, in all regions worldwide.

Kasey Bamberger’s business earns carbon credits when it uses regenerative techniques to improve the soil.

Grounds for gains

The agricultural products and services sector has its own role to play in the growth of regenerative farming. “Our agricultural food system will undergo an accelerated transformation in order to provide enough healthy and affordable food for ourgrowing population. At the same time, it will need to mitigate its impact on our planet,” says Dirk Voeste, Senior Vice President Regulatory, Sustainability & Public Affairs at BASF’s Agricultural Solutions division, Limburgerhof, Germany. “At BASF we are helping farmers worldwide, like William Pitts and Kasey Bamberger, to tackle the most pressing climate challenges. We provide the right combination of technologies to increase yield with reduced environmental impacts, and make their farm management easier and more effective. And we are exploring ways to help incentivize carbon efficiencies.”

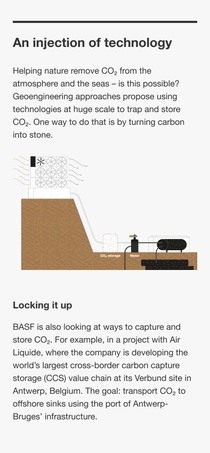

The company has committed to enabling a 30 percent reduction in CO2 emissions per ton of crop by 2030. As part of that effort, BASF launched its own Global Carbon Farming Program in 2022. Through a multi-year series of field trials, it aims to find the best ways to help farmers cut their carbon emissions and increase sequestration. It also includes a global framework that will allow farmers to access carbon credits from recognized certifiers.

And what does “the father of soil science,” Professor Lal say? “Payments

for carbon should be universally avail able to farmers. Let’s move away from subsidies and start paying for ecosystem services,” he says. “Let’s pay a fair price per ton for carbon sequestration in soil and trees. And let’s pay it transparently and directly to the people who do the work.”