Chemistry of feelings

They seem to have us completely under control, can plunge us into inner chaos or let us feel like we are floating on cloud nine. We are talking about hormones. In words and images, we show what lies behind our great emotions.

Hungry? Tired? On a high? We would not have any of these feelings without hormones. “Hormones are something like the background music to our existence – an atmosphere that is always there,” says German neuroscientist Dr. Franca Parianen, who focuses on hormonal activity as a science slammer – in bars, at medical congresses, and as the winner of the German Neurological Society’s neuro slam. “They are part of us, and they define us as individuals.”

The biochemical transmitters determine what makes us anxious or feel good, but also when we become sleepy or highly motivated. Our hormonal system is part of a sophisticated mechanism that makes our body work. “They can trigger complex processes,” Parianen says. “Short-term reactions like a moment of shock, but also long-term programs like puberty.” Hormones are composed mainly of Proteins or lipids, which are basic components of our organism. “But there is not just one single chemical structure – some hormones are very complicated, while others are very simple,” Parianen says.

The brain takes the first step in hormone production. It evaluates incoming information and sends signals to the producing organs, such as the thyroid, pancreas and adrenal glands. The transmitters pass through the bloodstream to their intended destinations, where they dock with the cells that are waiting for them. There they trigger the reactions intended by the brain – for example, short-term reactions in metabolism and circulation, or longer-term ones in growth or sexuality. They cause our emotions to ebb and flow. In other words, hormones are the chemistry of our feelings.

All in your head?

“Perhaps the simplest and earliest examples, the first demonstrations of body-to-brain communication, are the steroid hormones that regulate reproductive function: estrogens and androgens like testosterone,” says Dr. Donald Pfaff, Emeritus Professor of Neurobiology and Behavior at The Rockefeller University in New York, United States. Sexual hormones play a major role in shaping our brain even before birth. Early in our life, another hormone immediately gets involved: oxytocin, also popularly known as the “cuddle hormone.” It is not only responsible for the strong bond between newborns and their parents, but is also the glue for close social relationships during our lifetimes.

The sense of well-being extends to other areas of life. Oxytocin reduces stress, makes us less aggressive and consequently more compassionate. And this doesn’t just apply to human beings. Researchers at the University of Minnesota, United States, sprayed the bonding hormone into the noses of African lions. Afterwards, the predatory cats were much more relaxed and tolerated more closeness from other members of their species. An oxytocin effect can also be observed between human beings and their pets. Japanese scientists gave owners half an hour to talk to their dogs and to cuddle them with intensive eye contact. Their subsequent oxytocin levels were significantly higher – and this applied to both the two-legged and the four-legged participants.

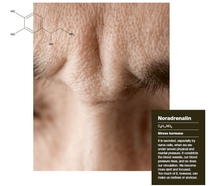

This means that our feelings are determined to a decisive extent by those transmitters. “It is hard to think of a hormone that is not influential on our emotions. Of course, only some of these are direct effects and there is a plethora of indirect ones,” Pfaff says. “Every hormone has a basic function, but what are known as epigenetic effects make way for individual experiences to influence how hormone effects work out.” This also explains why human beings handle stress in different ways. First, a standard program runs like this: Adrenaline and noradrenaline become active. Our heart beats faster, we breathe more deeply, our senses become heightened, and bodily functions such as hunger, thirst or pain close down.

We become instantly ready for action. “Our stress response is actually there as a survival mechanism,” Parianen explains. Today, though, even things like an important presentation, bungee jumping, or Sunday drivers on the roads can send our adrenaline levels through the roof.

When we are extremely agitated, this usually subsides again quite quickly, thanks to the programming of our hormones. However, if we constantly carry on like that, long-term stress is just around the corner. For our body, this means that the adrenal glands produce increased amounts of cortisol. That hormone can actually be good for us, as it makes us less sensitive to pain, for example, and inhibits inflammation. In the long term, however, a high cortisol level weakens the immune system. “Chronically secreted stress hormones are not good for the brain and can actually have an impact on its structure,” Parianen says.

Don’t stress about stress

The good news is that no one is completely at the mercy of their hormones, because “the interaction between hormones and behavior is bidirectional. Hormones can influence behavior, and behavior can sometimes influence hormone concentration,” says Professor Randy J. Nelson, a neuroscientist at West Virginia University, United States. With cortisol, this effect can actually be measured – specifically in hair, because it is deposited there.

The German Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences, Leipzig, and the Research Group for Social Neuroscience of the Max Planck Society, Berlin, took a closer look at this in a study. Test subjects each spent half an hour, six days a week, performing a mental training exercise that was intended, in particular, to strengthen their mindfulness and empathy. No stress about stress – the first effects were visible after just three months, and after six months their cortisol levels were on average 25 percent lower. Even in acute stress situations, such training exercises help people to keep a cool head.

“Interestingly, the things that stress us are often the same as those that motivate us positively,” Parianen notes. What is the difference? In particular, the level of perceived control. If we feel a loss of control, stress gains the upper hand. However, if we have control, situations which are a little stimulating and tricky are good for us. This is mainly down to dopamine and serotonin.

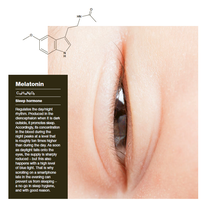

First, dopamine enhances our motivation. If the dopamine level is balanced, we find it easy to tackle things and pursue our goals. This does not have to mean starting with a triathlon – gardening, cooking, or learning a language can also provide a sense of achievement. The brain then releases serotonin. This transmitter is considered the happy hormone. However, it can do a lot more than lift your mood. Serotonin regulates hunger and body temperature, among other things. It is also part ofour biological clock.

Daylight and sunlight boost serotonin production. When it starts to get dark, our body converts serotonin into melatonin and we become tired. During the night, the melatonin level falls, while the cortisol level rises and makes us alert. Modern life can disrupt This sophisticated mechanism, with not much daylight, but brightly lit screens until late evening. This confuses our day/night rhythm. But Parianen is reassuring: “The crazy thing is that our sophisticated hormonal system is, on the one hand, so complex at the biological level, but on the other hand so uncomplicated that one can say movement, relaxation and sunlight are simply good for us.”